I spent the first years of the pandemic trying not to die. Not in the literal sense of taking precautions against a deadly virus, though I did that too. Not in the same urgent way as an ICU patient, septic and deoxygenating, though I was hospitalized occasionally. But in the most mundane, microscopic of ways: I caught COVID in March 2020 and my body forgot how to live.

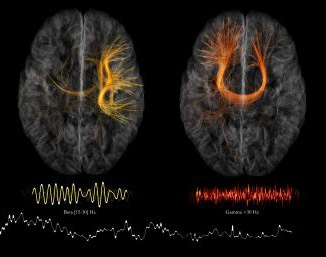

Supposedly automatic, innate processes broke down under viral damage and immune system hyperbole. My nervous and cardiovascular system couldn’t manage my heart rate, blood pressure, blood clotting, body temperature, inflammatory and allergic responses, the dilation and constriction of blood vessels, the digestion of food, the coordination of limbs and digits, or the oxygenation of tissue and muscle. Every regulatory process my doctors could and couldn’t measure, everything that keeps you uncomfortably up at night debating if you should call an ambulance, all the perceptions and adaptations that let you move through the world as a functional, self-preserving body, went slightly or seriously haywire.

I forgot how crosswalks worked and walked into traffic. I forgot to turn off the stove and melted tupperware and singed oven mitts and burnt meals and grabbed metal pot handles with bare hands. Once I left an entire carton of eggs on a hot element until it smoked with a rot I couldn’t remember how to smell. I forgot my doctors’ names and my own birthday and address. I forgot I had a mailbox and bills, forgot how to pay them and got every utility shut off like the cascading organ failure of household management. I forgot how to chop vegetables and how to use a can-opener and how to store leftovers. I forgot my girlfriend left me after the first year of illness and swam, disoriented and freshly grieving, in a dementia-like time loop. I fell asleep sure I was dying and woke more grave than bed.

It is cliche to start any story – especially on being ill – with it’s indescribability and the writer's attempts to carve it out with craft and wit and therapy. And yet, it has proved as impossible to capture Long COVID’s post-viral cognitive impairments as it was to extract basic nouns from the fog. Having an idea, even a not very insightful one, felt like throwing bubble bath at a wall. Following through was like trying to kick your legs out from under six heavy quilts. For a plurality of years, time looped like a noose around concepts that no amount of autocorrect could spell for me. I slept, and woke, and blacked out, and tried to write texts or emails or social media posts or symptom logs to communicate my situation sufficiently to get professional or communal help. Nothing, not the events that passed and passed me by, not my medical file, not the global or personal responses to my situation, made sense.

This substack is a long-form, serialized experiment; a craft exercise in sifting ideas from poetry to prose, and back again; and a story it has taken me 3+ years to reteach myself how to write. Written with love for everyone who has gotten sick and those who have always been sick. Launched long past the cultural moment when personal stories of the more horrific, less headline-worthy aspects of long covid were of widespread interest and into a broken media landscape in which content distribution is fractured. In the hopes of lighting the way a bit for those that come after me in subsequent waves and capturing what research has failed to describe and public policy has failed to address. On halloween, because this is a kind of ghost story.

Part science journalism, part body horror, part lyric essay, part policy analysis, part poetry. All true, even the monsters.

Dear Impairing Curse Author,

Thank you for this beautifully written post. I have tears in my eyes. You have evoked memories of my own challenges and the pain of so many others who have experienced Long COVID.

You are a beacon for the tens of thousands of LC patients. I hope that others will take the time to read your post.

Kind regards,

Mardi

You are a fantastically talented writer! Thank you so much for sharing, for using your gift to reach so many. I look forward to reading more.