We keep each other alive

Sit sweet-mouthed in the doctor’s office in your best ‘reliable witness’ costume, ghosts braiding your hair. Appear ill but not in need. Competent but not complicated. Well-

spoken but not too prepared. Memorize side effects. Dress neatly. Smooth your skirt, still your face. Controlled substances mean you can’t cry if she says no. Good

girls don’t want it this bad so you don’t tell her about the haunting. How they find you crumped on your own doorstep trying to get your shaking

keys through the door. How they paint you into bed, legs calved in metal. You don’t tell her about the days spent unhooking yourself from well-meant prescriptions. But what do you know

better than your own body. Your own fever. Your own hands on your brow. Your own stealth. Your own storms. Your own

sorry. Your own safety. Your own pain. Your own falls. Your own fault. Your own fault. your own body and it’s haunted halls and absentee owner.

(first published in Minola Review, Issue 21)

There is an art to making the medical system work for the patient, to present in such a way that it spits out the recommendation you want or the tests you need, to pull the right bureaucratic levers so the alarm rings just loudly enough to move you swiftly through the machinery and handle you with care.

It is not always comfortable to question authority and protocols, to presume you know better than highly-educated professionals, or that your situation is more dire than everyone else waiting in line. It requires simultaneously holding the beliefs that you are severely, incontestably ill (regardless of your often benign test results) and that this complex disease process is intervenable, but beyond of the scope of your own lifestyle and environmental interventions. It requires, ironically, a significant amount of executive function, problem-solving, verbal fluency, and emotional control, all of which suffer when the body is in pain or ill-equipped for the day’s energy expenditure requirements.

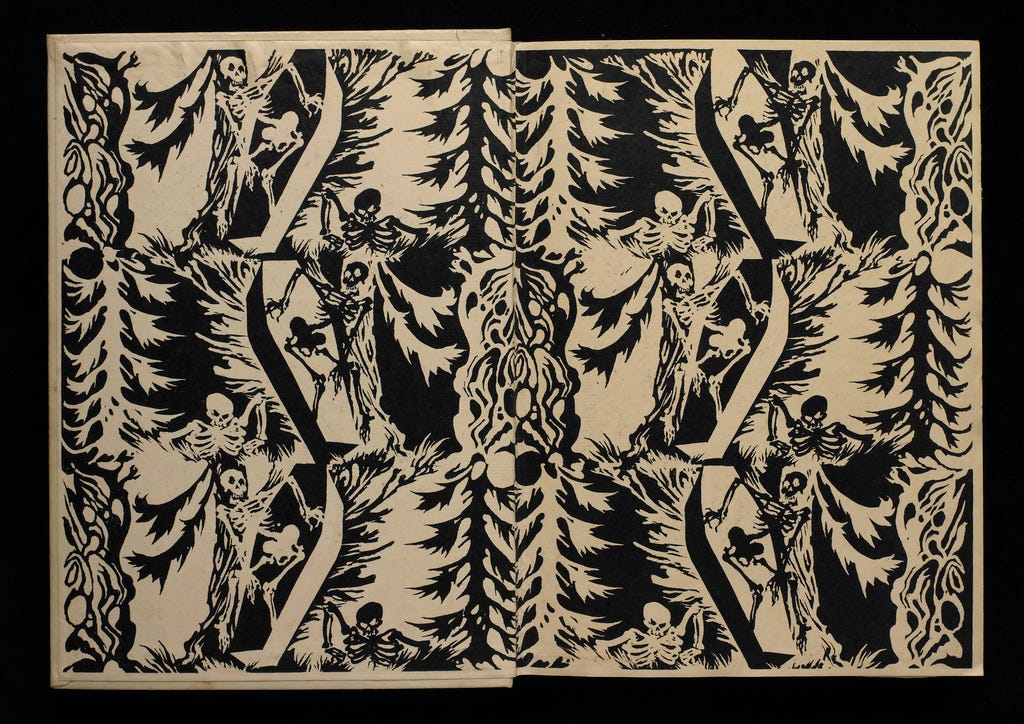

Behind many a chronically ill person in a doctor’s office, there is collective invisible patient labour sharing specialist referrals or medical history briefing binder templates, loaning sample medication, explaining test results, or scripting symptom recitation prayers into the capitalist frame of “impeding tasks of daily living and ability to work”, particularly in the moments when we are least able to do this labour for ourselves.

“We keep each other alive” is a refrain I say to and with other disabled and chronically ill friends to describe this labour. It is specialized intra-communal care, beyond meal trains and ride-shares, a resource for when the medical system and the broader social system is wholly disinterested in our survival, the empowering opposite of police wellness checks, the hands-on support we need far more than empathy.

It is a mostly invisible community that is often too sick to be in the world — not the instagrammable blood family of Christmas or the chosen family of New Years and birthdays but a secret third thing. In this season especially I am reminded how much of a performance community can be. Queer community is sometimes just the tinder matches you never met up with, the hostile exes on the sidelines of your community sports games or in the audience at karaoke, the chess board of failed connections all trying to look desirable and unaffected and without regret at the same weekly events, the ways we flag social affiliation and orientation and power.

It is the gossip we don’t believe and the gossip we do; the abusers and poor behaviour we can’t name because they host the fun parties or have otherwise knit themselves self-protectively into critical infrastructure and gatekeeping roles. For me, it remains a tangle of people who won’t take precautions to protect each other or will not forgive me for communication missteps made while trying not to die.

In this mess of a social landscape and medical system, “we keep each other alive” is a mutual promise and investment in each other’s continued survival and worthiness of care and communal access. I’m alive thanks to patient-led research and advocacy; the early pandemic patient-moderated online forums; and the endless patience of patients, many of whom are or have been bedbound or housebound. My DMs hum with medical gossip and N=1 data, friend-of-friend referrals seeking advice and crip doula support, sharing the latest studies or which doctors are accepting patients and what rituals to perform to enrol, calculating each other’s pulse pressure or medication half-life, studying up on the mechanisms of action behind rare side effects, or joking about the mundane grossness and inconvenience of illness.

I am alive today thanks to the diagnostic, research, and referral labour of friends without medical degrees; who will not let each other give up and accept an intolerable, declining, and dangerous health status quo; who see each other as endlessly interesting solveable problems.

The Impairing Curse is a long-form, serialized experiment in personal essay, science journalism, policy analysis, and poetry. To start at the beginning and read it in order, go to the first essay or read about the aesthetics and labour of illness, the science of salt, and the failures of public health. To support this project, share it online or subscribe. The series is intentionally not behind a paywall, to ensure broad access to patients and timely circulation of information in our evolving public health crisis, but paid subscriptions are welcome.